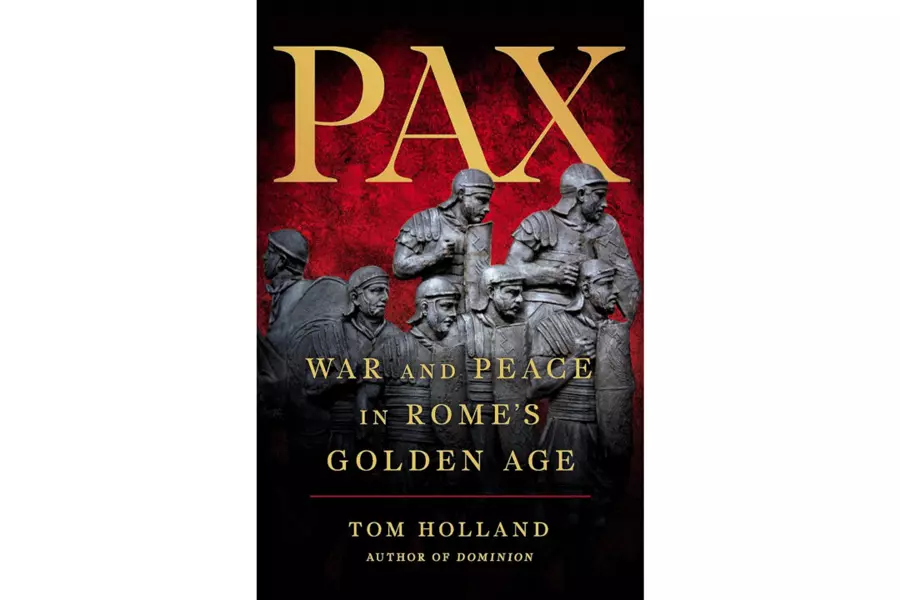

The Roman Empire’s journey from Nero to Marcus Aurelius, as detailed in Tom Holland’s latest book “Pax: War and Peace in Rome’s Golden Age,” is a tumultuous, blood-stained odyssey through the reigns of the empire’s 1st and 2nd century emperors.

Following Caesar Augustus’s victory over his internal enemies, Rome experienced a period of tranquility within its borders. Despite external conflicts that were often perceived as peace compared to the internal strife that had previously plagued the city from Sulla’s civil war to Julius Caesar’s and Augustus’, the Roman Republic had transformed into an autocratic empire with a veneer of republicanism.

Holland quickly traverses through emperors in the wake of Caesar’s ascension, delving deeper as he reaches Nero’s rule. Despite his lack of military experience, love for acting, and his bizarre obsession with his deceased empress that led to the creation of an empress from a boy, Holland argues that Nero managed to maintain peace within the empire. However, power proved elusive, as justified paranoia led to Nero’s suicide, leaving the empire without a successor and in a state of chaos and confusion, marking the end of a century-long ‘peace.

As chaos grips Rome, Holland takes us outside the city limits to the far reaches of the empire. Here, he introduces two future emperors – Vespasian and Titus – during the Jewish revolt in Jerusalem. Holland explores the siege of Jerusalem, a misunderstood prophecy that led to the city’s destruction, and the subsequent diaspora, highlighting Vespasian’s decision to retain a Jewish sage who predicted his rise to power.

In addition to the Judaeans, “Pax” presents other formidable adversaries like the Germans, Britons, and Dacians. Holland emphasizes throughout the book that these enemies posed more than just military threats. Upon conquering nations and tribes, Romans frequently pursued peaceable relations with them, leading to the permeation of foreign cultures not only within the empire but into Rome itself.

Holland’s narrative spans a range of Roman history and various themes, sometimes loosely organized, making it difficult to discern one central theme. However, the risk of diluting a nation or empire’s core cultural norm – its religion – seems to rise above the others. This risk is demonstrated in the book’s conclusion, as Holland briefly mentions Aurelius’ arrival and his place among the Five Good Emperors. Yet, what follows after is inevitable: not the end of peace, but the end itself. This frightening prospect resonates for any nation or empire that has undergone significant change and cultural dilution.